JANUARY: Justice

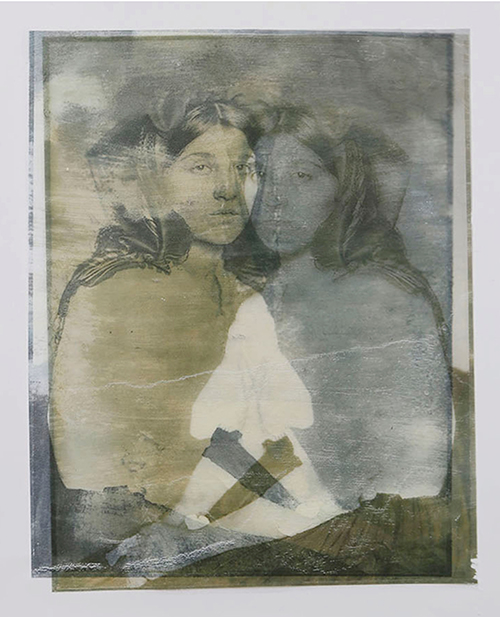

‘Isabella’

Solvent Transfer on Watercolor Paper, 2017

By Linda Smith

Curator’s Note

by Gal Cohen

‘Isabella’ is a mixed-media work showcasing a 1911 young immigrant from Italy to the US. It’s part of the series “Sojourners,” where Smith manipulates archival photographs of family members who immigrated from Italy to the US to echo the cross generational complexities that are inherited to the process of Immigration. The haunted look on Isabella’s face and the ghostly reflection of her image speaks to the rooted conflict and collective memory of the migration and immigration movements — the vulnerability and displacement, along with the reinvention of life itself, embedded with hopes for a safer, brighter future. Questions of justice, equality, and human rights are key to processes of migration and immigration around the world, as the wide range of by-choice migrants, through refugees and asylum seekers reveal the built-in inequality in contemporary societies, especially amidst the current global refugee crisis.

About the Artist

Linda Smith is an artist and art educator, who started a non-profit organization while living in Kigali, Rwanda, called the TEOH Project, which provides cameras and art classes to children in Rwanda, Ghana, and the Bronx. She has been commissioned by the United Nations to provide photography classes to survivors and former perpetrators of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. She earned her BA from Syracuse University, MA in Communications at Goldsmith College at the University of London, and MFA from the University of Connecticut. Her work has been exhibited in the United Nations, embassies, and universities.

Justice

By Rabbi Ari Perten, Norman E. Alexander Center for Jewish Life Director

Justice is at the center of the American myth. The average school day begins with a recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance in which students declare the US to be one nation… “with liberty and justice for all.” Though this mantra is so regularly repeated, our lived experience often indicates that justice is, perhaps, not always the reality which we experience, but rather a dream towards which we aspire.

The classic image of justice (based on the Roman goddess of Justice, Iustitia) is a blindfolded woman with a set of scales in one hand and a sword in the other. This representation plays on the concept of sight asserting that justice needs to be impartially applied without regard to wealth, power, or any other status. In the Midrash Tanhuma (Shoftim 8:1), we are reminded, “When the judge sets his heart on a bribe, he becomes blind to justice and is unable to judge [a case] honestly.” Justice must be directed without the imposition of external factors. When sight is allowed, it clouds judgement, distancing justice from its appropriate application.

Interestingly, in the book of Deuteronomy (22:1-3) there is an explanation as to the application of justice in the return of lost property that also utilizes the image of sight. The final verse insists, “and so too shall you do with anything that your fellow loses and you find: you may not hide yourself.” The medieval French commentator, Rashi, remarks on this final injunction, “You must not cover your eyes, pretending not to see it.” Here, playing on this same theme of sight, Rashi insists that justice can only occur when we actively pursue sight, removing any blindfolds that might limit the ability to see.

As our country continues to struggle with the concept of justice, we must each ask, what is my understanding of justice?