MAY: Honor

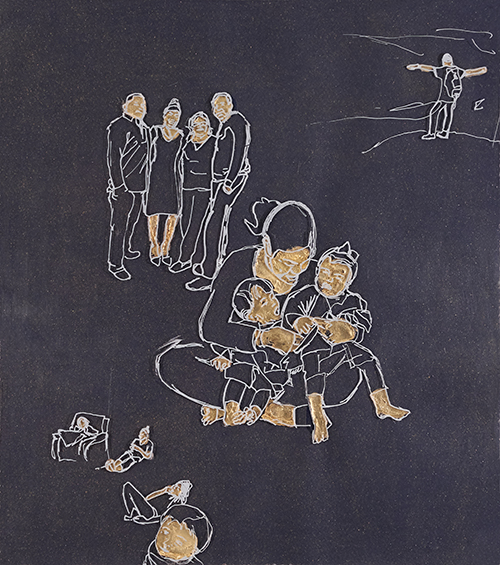

The Significance of Motherhood, 2020, Gold leaf, fabric and flashe paint on plexi, 20”x 20″

The Only Thing that Matters, 2020, Gold leaf, paper and paint marker on plexi,

15″ x 17”

By Dianne Hebbert

Curator’s Note

by Gal Cohen

Maya Ciarrocchi’s art practice speaks strongly to the value of Remembrance. Through personal narrative, research-based storytelling, and embodied mapmaking, Ciarrocchi’s works recreate access to the stories of perished communities and demolished places, thus exploring the physical and emotional manifestation of loss. This still image was captured from an in-process interdisciplinary performance work: Site: Yizkor, commemorating the Jewish communities who perished during the Holocaust. Among the source material included, there are architectural renderings of demolished buildings, memory maps of vanished places and figures, and prose remembrances obtained from historical Yizkor books. This month, when Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day is observed, Maya’s work resonates and invites us to dive into the remembrance of these lost communities.

About the Artist

Dianne Hebbert is a Nicaraguan-American artist and curator. She works primarily in painting, printmaking and installation art. As a Miami native she attended New World School of the Arts before she earned her BFA in Painting and Drawing from Purchase College and her MFA in Printmaking from Brooklyn College. Hebbert is a recipient of the Vermont Studio Center Fellowship and residency, she was selected as a Smack Mellon Hot Pick Artist in 2017 and an Emerging Leader of New York Arts 2016-2017 Fellow. Hebbert has completed residencies at Trestle Art Space, Constance Saltonstall Foundation for the Arts and is currently a Chashama Space to Connect artist.

Remembrance

By Rabbi Ari Perten, Norman E. Alexander Center for Jewish Life Director

The Latin phrase nomen omen suggests that something’s name gives insight into its essence. Such a statement is certainly true for the concept of honor. In hebrew the word honor כבוד (kavod) comes from the root כ.ב.ד (k.v.d) meaning weighty or heavy. The diametric opposite is the word for curse, קלל (klala) which comes from the Hebrew root ק.ל (k.l.) meaning light. An implicit message from this etymology is that to honor someone means to treat them with due and deserved seriousness. While to curse someone is to treat them lightly. Conceptually, such an assertion is not terribly challenging. Intellectually it is easy to espouse the value that every person is deserving of honor, that every person deserves to be taken seriously. Yet our lived experience so often tells a different tale. Often we live in the margins, either exuberantly clinging to (and at times even magnifying) our own importance, or, the opposite seeing ourselves as unimportant, common, and meaningless. In both moments of extremes we would do well to remember that the value of honor insists on our essential substance. As people we are worth honor and such a statement is not uniquely limited to our existence. Observing pleasant sights, smelling an appealing odor, savoring a delicious taste all, almost naturally, elicit reflexive praise. If the inanimate can be deserving of such honor, how much the more so beings endowed with intelligence and understanding. How do you see honor in yourself and honor in others?